Eddie Rickenbacker the Racer and Ace

Like many young men of his era, Eddie was obsessed with technology and speed. The automobile combined both, and it became one of his life-long passions. Eddie saw his first automobile around 1905, a two passenger Ford runabout, and was instantly smitten. His stint in the machine shop of the Pennsylvania Railroad, combined with his lust for adventure and thoughts of the Ford, lured him into the brand new automobile industry.

Eddie began his automotive career in the Evans Garage. To upgrade his mechanical skills, he took a mechanical engineering course from International Correspondence School in 1905. He successfully campaigned that same year to land a job with the Oscar Lear Automobile Company in Columbus, working for Lee Frayer. Eddie worked for the Oscar Lear Automobile Company until 1907 when he followed Lee Frayer to the Columbus Buggy Company.

The photograph shows Eddie in a Firestone-Columbus, driving orator, statesman, and politician William Jennings Bryan (seated behind Eddie) on a Texas speaking tour in 1909. Eddie was in Texas helping the Columbus Buggy Company establish dealerships for the Firestone-Columbus and offered to drive Bryan as an advertising stunt.

The photograph shows Eddie in a Firestone-Columbus, driving orator, statesman, and politician William Jennings Bryan (seated behind Eddie) on a Texas speaking tour in 1909. Eddie was in Texas helping the Columbus Buggy Company establish dealerships for the Firestone-Columbus and offered to drive Bryan as an advertising stunt.In 1910, working as the Columbus Buggy Company's branch sales manager in the mid-west, Eddie entered his first race as an advertising gimmick for the Firestone-Columbus Motor Car Company. He raced a stripped down Firestone-Columbus on a dirt track in Red Oak, Iowa. He exited the race after an accident. Eddie raced in the first Indianapolis 500 on Memorial Day, 1911. He raced for the Columbus Buggy Company until 1912, when he left to become a professional racer. He raced for a second rate team called the "Flying Squadron" until the end of 1912, when he took a job with Fred and Augie Duesenberg at the Mason Company. After a brief time racing for Peugeot and Maxwell, he was named manager of the Prest-O-Lite Racing Team. He raced for Prest-O-Lite until the end of 1916.

With the war dragging on in Europe, it became apparent that the United States was going to "toss its hat in the ring" and send troops to the war zone. Eddie enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1917 when Major Lewis Burgess, who was also a racing fan, asked him if he would like to go with General Pershing as one of his chauffeurs. Eddie Rickenbacher would never race cars again.

With anti-German sentiment growing in the United States because of the war, Eddie Richenbacher changed his name to Rickenbacker, because Eddie thought it didn't sound so German.

World War I

Eddie enlisted in the U.S. Army in May, 1917 as part of the American Expeditionary Forces and arrived in France on June 26. He was assigned as a staff driver for General John Pershing at the rank of sergeant first-class, but what he really wanted to do was fly. With the connivance of high-ranking friends in the AEF (especially Billy Mitchell), Rickenbacker was accepted into the Army Air Service even though he was two years over the age limit. He trained at the 2nd Aviation Instruction Center in Tours, France.

With his training complete, he was commissioned as a 1st Lieutenant and became chief engineer at the poorly prepared training base in Issodun. After making many improvements at Issodun, he was sent for training in aerial gunnery in Cazeau in January, 1918. He qualified as a candidate for training to become a combat pilot instead. Because of an old injury to his cornea they felt he would never do any better than average at operating the machine gun.

In February, Eddie was sent to Villeneuve-les-Vertus for advanced training and was assigned to the 94th Aero Pursuit Squadron, the first all-American air unit to see combat (April 14, 1918). He received training there from Raoul Lufbury, a veteran of the Lafayette Escadrille. He would fly both Nieuport 28s and Spad XIIIs in combat.

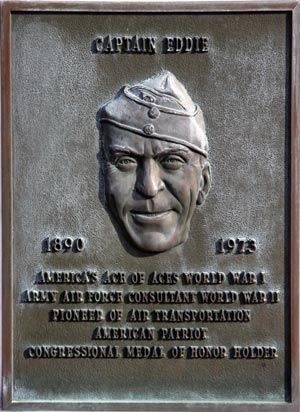

Eddie had his first confirmed victory on April 24, 1918 and in May, he became an ace and won the French Croix de Guerre by shooting down 5 German airplanes. He was named Commander of the 94th, the "Hat-in-the-Ring" Squadron, on September 24, 1918. The following day, Eddie shot down 2 more German airplanes, victories for which the United States awarded him the Medal of Honor in 1930. His 26th confirmed victory occurred on October 30, and the last victory (the 69th) for the 94th occurred on November 10, 1918. World War I ended the next day. Eddie returned home in 1919 as America's "Ace of Aces."

After Eddie returned from World War I as America's hero, he was linked romantically by the press with a variety of women. However, given the grueling travel schedule he kept, he didn't have time for romance. That changed in 1921, when Eddie renewed his acquaintance with Adelaide Frost Durant, whom he had known on the auto racing circuit.

Adelaide was a beautiful and wealthy divorcee. Her first husband, Cliff Durant, was a race car enthusiast and driver and son of General Motors founder William C. Durant. Their courtship was brisk, and they married in the Cumberland Presbyterian Church of South Beach, CT, before a small party of witnesses (including Eddie's childhood minister) on September 16, 1922. Eddie announced the marriage to his mother that evening via telegram. He and Adelaide honeymooned in Europe.

In the diary that Eddie kept during their honeymoon, he writes, "Like a child with its first real toy am I, only the most beautiful toy, not in the true sense of the word but in the form of a wonderful Pal to share and suffer through life alike." When they returned home, they settled in Detroit, Michigan. Before the end of the decade, the Rickenbacker's adopted two sons, David Edward in 1925 and William Frost in 1928.

Adelaide was an unconventional wife for the times: she was 5 years older than her husband, and was very outspoken. As independent as she was, Adelaide fully supported Rickenbacker's endeavors until his death in 1973. In 1977 at the age of 92, Adelaide being completely blind, in failing health and severely grieving the loss of her husband, shot herself at her home on Key Biscayne, Florida.

Up through 1927, Eddie was a partner with Byron F. Everitt, Harry Cunningham and Walter Flanders in the Rickenbacker Motor Company, manufacturing a car he claimed to be "worthy of its name." The company used the Hat in the Ring symbol from Eddie's World War I fighter squadron to market the car. Unusual in appearance, the Rickenbacker autos incorporated highly-advanced systems such as 4-wheel brakes that later became common on all cars. However, the company over-pursued technology resulting in an automobile that was too advanced for their time, and consumers were not sure of the benefits the car provided forcing the Rickenbacker Motor Company into bankruptcy.

Undaunted by financial failure, Eddie raised $700,000 to buy the Indianapolis Speedway in 1927. The "Brickyard," as it was called, was host to the most famous of all American automobile races, the Indy 500. Having raced in the first Indy 500 in 1911, he knew the importance of the race as a testing ground for automotive technology.

Eddie closed the Speedway during World War II. By the time the war was over, his attention had turned toward running Eastern Air Lines. The repairs needed to make the Indianapolis Speedway usable after years of neglect were too much for Eddie. He sold the track in 1947 for what he had paid for it. Nevertheless, Eddie stayed in contact with automotive racing for the rest of his life.

World War II

As war was breaking out in Europe and Asia, Rickenbacker vehemently opposed the United States' entry into the war and even joined the "America First" committee. However, once the United States committed itself, Eddie supported the war effort, although he spent the first 3 months of the war recuperating from an airliner crash (shown at left recuperating after the crash).

Flying on business on an Eastern Air Lines DC-3, the plane crashed outside of Atlanta. In spite of his own critical wounds (a dented skull, other head injuries, shattered left elbow and crushed nerve, paralyzed left hand, broken ribs, a crushed hip socket, broken pelvis, severed nerve in his left hip, and a broken left knee), Rickenbacker somehow encouraged uninjured passengers to get off the plane and find help. They were eventually rescued after spending the night at the crash site. Rickenbacker barely survived, and the press had even announced his death.

At the request of General H. H. "Hap" Arnold, Eddie toured Army Air Corps training bases throughout the southeast during March and April of 1942 to bolster morale, impress pilots with the seriousness of their mission, and secretly examine the bases and training pilots were receiving.

In September, Secretary of War Henry Stimson asked Rickenbacker to tour bases in England "as a continuation of your tour of inspection" and to seek out evidence of espionage. Rickenbacker returned from England in October. Stimson immediately sent him on a tour of the Pacific theater.

In October, 1942, leaving from Hawaii on a mission to deliver a top secret message from Secretary Simson to General Douglas Mac Arthur, Eddie and his aide, Colonel Hans Adamson, boarded a B-17. The poorly prepared B-17 took off for a refueling stop on Canton Island. Due to inadequate navigational equipment and a faulty weather report, the B-17 overshot its mark. Hundreds of miles off-course and out of fuel, Cherry ditched the plane in the Pacific.

The eight men on board lashed together 3 rubber rafts so they would not get separated. They thought that rescue would come quickly because of Rickenbacker's fame, but they remained lost at sea for 24 days. Their meager supply of food ran out after 3 days, but on the 8th day a sea gull lighted on Eddie's head. The unfortunate bird became dinner and fishing bait.

On the home front, Eddie's wife Adelaide remained optimistic that Eddie would be rescued. When it appeared as though General "Hap" Arnold was giving up on the search, she stormed into his office and practically tore the decorations off his jacket, demanding that the hunt continue. Navy pilots finally found and rescued the crew in the Ellice Island chain on Friday, November 13, 1942, more than 500 miles beyond Canton Island. The rescue came too late for Sergeant Kaczmarczyk, who died after 2 weeks at sea.

Suffering from exposure, dehydration, and starvation, Rickenbacker rested a few days then proceeded on his original mission, including inspections at facilities at Port Moresby, Guadalcanal, and Upola. He reported to Secretary Stimson and General Arnold on December 19, and then returned to New York the following day where he was reunited with his family.

In April, 1943, Eddie took on yet another assignment for Stimson, this time visiting bases and production facilities in North Africa, the Middle East, India, Burma, China, the Aleutian Islands, and the Soviet Union.

Life at Home

Adelaide and Eddie's marriage lasted until his death in 1973, a total of 51 years. Eddie credited Adelaide with saving his life twice. The first time was after his near-fatal airplane crash near Atlanta, Ga. While he was in the hospital, fighting for his life, his oxygen tent malfunctioned. According to W. David Lewis, "One night Adelaide awakened with an overpowering sense that he was dying. Dashing up a flight of stairs and down a hallway to his room, she found an attendant asleep at the door and saw that Eddie had ripped the tent apart in the ferocity of his struggle to live. After saving him from suffocation, she exploded at the staff for its negligence."

The second time was when he was lost at sea in late 1942 crash of the B-17.

A great deal of son William's correspondence with Eddie survived. The correspondence between Eddie and Bill, from around 1936 until just before Eddie's death in 1973, demonstrates a strong bond of affection between father and son. Bill also attests to this affection in his 1970 book, From Father to Son: The Letters of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker to His Son William, From Boyhood to Manhood. Though loving, Eddie held his sons to high standards of conduct. He required that they live up to his ideals of hard work and honor as well.

Next: Rickenbacker and the Airlines

See also: