Early History of Franklinton

Early History of Franklinton

Before Columbus was established, the land east of the Scioto was mostly uninhabited and heavily forested. There were several Indian Mounds in the area. The area was designated as part of the Refugee Tract which was land set aside for residents of Nova Scotia that supported the American Revolution. However, when the Revolutionary War came to an end, they found themselves on the short end of the stick when the new American government gave up any claim to Nova Scotia and left it for the British. In an effort to make things right, the federal government gave these families land in the Ohio Territory. However, most of them decided not to make the treacherous move to the Ohio frontier and opted instead to sell their land rights to land speculators. That is the reason Lucas Sullivant established Franklinton on the west side of the Scioto, as this land was available for purchase, even though it was clear the Scioto frequently flooded the area with devastating results. The frequent flooding of the area also created superior top soil for growing corn.

Lucas Sullivant, who was by trade a surveyor. He had ventured several times in the previous 5 years into Ohio along the Scioto River, but not until 1795 did he get as far north as Central Ohio. On that trip Sullivant brought a group of 20 men, mules, horses and supplies up along the Scioto River from Kentucky. His job: survey the western side of the Scioto River near the confluence of the Whetstone River (now called the Olentangy). Risking encounters with Native Americans that regularly passed through the area, Sullivant completed his task, they returned to Kentucky. In payment for his work and leadership, Sullivant was given several thousand acres at the confluence. He returned to the area in August of 1797 and began the task of laying out a small town.

The name he chose for the new town was Franklinton, in honor of Benjamin Franklin who had died just a few years before. Franklin, a world famous celebrity and founding father of the United States, was a man that Lucas Sullivant admired deeply for his courage, ingenuity, and his strong business sense.

The plot of land that Sullivant was given was part of the Scioto River Basin, a wide even plot of land between two heavily wooded areas to the east and west. This land was extremely fertile and the Indians had used it frequently in the past to grow corn. The disadvantage of the land was that it was prone to frequent flooding which Sullivant would soon realize.

The plot of land that Sullivant was given was part of the Scioto River Basin, a wide even plot of land between two heavily wooded areas to the east and west. This land was extremely fertile and the Indians had used it frequently in the past to grow corn. The disadvantage of the land was that it was prone to frequent flooding which Sullivant would soon realize.

At that time the Scioto River was a much deeper river than it is today. Today we see a river that only seems to flow when there are heavy rains. It's hard to imagine the Scioto River as being anything more than the docile river it is today. When Sullivant came to the area, it was well before the 2 large dams north of the downtown had been built for drinking water reservoirs. Those dams greatly reduced the river's water flow and cut down the amount of flooding. But in Sullivant's day, the river was a much wilder beast that would often rise up from its banks when heavy rains persisted.

Sullivant spent that winter laying out the town near the shores of the river. In the spring of 1798, the river rose up and submerged most of the newly plotted town. Not to be discouraged, Sullivant started over and moved the town just less than a mile away from the Scioto.

There were a few people that moved to the area in 1797-1798. To encourage more people to the area, Sullivant designated free land for anyone willing to build a house in the new town. Those wishing to take advantage of this offer, could select their own plot on the aptly named Gift Street (still in existence) which was within one block of the western limit of the town.

The town was laid out in blocks of 4 lots each. Each lot measured 99' wide by 115' deep and each lot abutted in the back with the next street's lots.

Sullivant built a jail, a courthouse, his brick house, and a brick church for his new wife Sarah. Sullivant also built the first bridge across the Scioto in 1815 that connected to Broad Street on the east. Foot passengers were charged 3 cents to cross; a mule, horse, or ass one year or older cost 4 cents; for each horse and rider it cost 12 1/2 cents; every 2-wheeled carriage 37 1/2 cents; and for 4-wheeled carriages, it cost 75 cents. Military and mail carriers could pass over the bride for free.

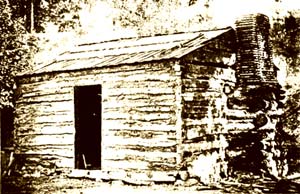

Lucas Sullivant Land Office and site of the soldier encampment during the War of 1812. Located just north of Broad Street on the west side of Gift Street.

Just before Columbus was established as the new state capitol, it was said that there was not a chair for every 2 persons in the county, nor a knife and fork for every 4 people. It was a compliment to say that a man would fight, and it was derogatory to say that he refused to drink. There was however, one virtue among the residents of Franklinton: they offered hospitality to anyone and everyone that stepped foot in the small town.

The War of 1812

By 1812, there were only a few hundred people in town. Yet, that was the year that would be the beginning of the greatest prosperity for the village, as well as the beginning of its demise and both occurred on the same day: June 18, 1812. When the second war with Britain broke out in 1812, it was on the same day that the first lots were sold to the public in Columbus for between $200 and $1000 each.

With the outbreak of war, Franklinton's population and importance would swell. Yet with the beginning of Columbus, Franklinton was destined in time, to become less important, and finally to be swallowed by the infant city.

As the news of the war reached Franklinton, a contingent of volunteers were assembled in Franklinton (3rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment). They soon departed for Urbana where they joined up with other regiments. From Urbana, the force marched north towards Detroit, constructing block houses as they went. However, when the group reached Detroit on August 8, they came into contact with British forces and promptly defeated. General Hull surrendered his forces to the British.

News of this defeat immediately swept through Franklinton. Fears that Indians would soon attack, brought settlers into Franklinton for security. Plans were developed for the defense of the town. Scouts were sent out to watch for advancing war parties. In the meantime,the governors of Ohio and Kentucky scrambled to recruit new troops to recapture Detroit. Franklinton because of its central location, was chosen as the rendezvous and depot of supplies for the new army.

General William Harrison Headquarters in Franklinton

On October 25, 1812, General William H. Harrison along with 3 other generals arrived at Franklinton where over 700 men had already assembled with more coming from Pennsylvania and Kentucky. To help reduce the threat of Indian attacks, General Harrison sent an expeditionary force of 700 from Franklinton to the present location of Muncie, Indiana. This force caught the Miami Indians by surprise on December 17. After that engagement, the military forces returned to Franklinton with much celebration.

Above is the actual 1812 weather vane from the top of the courthouse that Lucas Sullivant had built. The holes and dents resulted from bullets being fired at the vane for target practice by troops stationed in the field next to the building. Original weather vane is on display in the museum at Fort Meigs in Toledo.

In the meantime, additional men and provisions were arriving almost daily in Franklinton. Harrison began moving men and supplies from Franklinton northward to Upper Sandusky where a second effort to reclaim Detroit was made, with much the same results as the previous assault, resulting in the loss of an additional 800 soldiers. Renewed efforts by the governor to muster additional men for the fight brought more men into Franklinton. Once they were mustered in, they were sent north. One of the companies formed was under the direction of Brigadier General Joseph Foos of Franklinton.

On June 21, 1813 a council of the chief and the principle men of the Wyandots, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca tribes, about 50 total, met in Franklinton at Lucas Sullivant's house. The Native Americans had come to meet General Harrison about the ongoing war.

James B. Gardiner, the editor and proprietor of a weekly paper published in Franklinton, called the Freeman's Chronicle, was present, and in the next issue of his paper published on the 25th of June, 1813 printed a report of that meeting:

"After some preliminary remarks of a general character, General Harrison said to the Indians: 'That in order to give the U. S. a guarantee of their good dispositions the friendly tribes should either move with their families into the settlements, or their warriors should accompany him in the ensuing campaign and fight for the US.'

To this proposal the warriors present unanimously agreed and observed that they had long been anxious for an opportunity to fight for the Americans."

For the citizens of Franklinton, this was a particularly spectacular day. They were witnessing not only a massive uniformed miliary assembly, all standing at attention, but also opposite them a large group of seated Indians smoking pipes and paying little attention to the General Harrison's speech. When the general finished speaking, Tarhe, a Wyandot chief, stood slowly and made a brief reply. Then as a group, the Indians moved forward to shake hands with Harrison signaling their agreement with Harrison's wishes that the Indian Nations gathered, refrain from joining the war with the British. Once the meaning of these actions were explained, they were jubilant. It was reported that strong men and women openly wept for joy.

See also: